The Anglo-American War of 1812 must count as one of the most unnecessary conflicts in world history. Certainly, the last major battle of the war in which Andrew Jackson (who in 1829 would become the 7th President of the United States) defeated Major General Edward Pakenham, the Duke of Wellington’s brother-in-law, at New Orleans on 8 January 1815 was wholly unnecessary. The war had been brought to a close a fortnight earlier by the Treaty of Ghent on 24 December 1814.

The United States had declared War on the United Kingdom on 16 June 1812. The ostensible cause for the US declaration of war was a series of trade restrictions introduced by Britain to impede neutral trade with Napoleonic France with which Britain was at war. The United States contended that these restrictions were contrary to international law. The Americans also objected to the alleged impressment (forced recruitment) of US citizens into the Royal Navy. Another major source of American anger was alleged British military support for American Indians who were waging war against the United States.

The most obvious respect in which the Anglo-American war of 1812 was unnecessary lies in the fact that Lord Castlereagh, the British Foreign Secretary, had removed the United States’ principle casus belli by announcing a relaxation of the British restrictions six days before the US declaration of war. Both the War of 1812 and the Battle of New Orleans were in large measure the product of the limitations of early 19th-century trans-Atlantic communications.

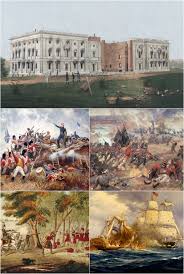

A number of campaigns may be readily identified but here we are concerned only with the Chesapeake Bay campaign conducted by Major General Robert Ross in the summer and early autumn of 1814, the highpoint of which was the British occupation of Washington and the burning of the Capitol and the Executive Mansion (normally referred to today as the White House) and several other public buildings.

Robert Ross was born in 1766 in Ross-Trevor (now Rostrevor), County Down. He graduated from Trinity College, Dublin, and joined the British Army. During the wars against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France Ross saw significant action in Spain, Egypt, Italy, and the Netherlands. He was thrice wounded. On two occasions his wounds were severe. For his conspicuous gallantry, leadership, and heroism, he was awarded three Gold Medals, the Peninsula Gold Medal, a Sword of Honour, and he received the thanks of Parliament.

Although a strict disciplinarian who drilled his men relentlessly, Ross was extremely popular with his men because of willingness to share in the hardships of his soldiers and fight alongside them in the thick of battle, a fact evidenced by his three wounds. By 1812 Ross was a Major General.

On 19 August 1814 Ross and 5,400 British troops, many of them veterans of the Peninsular War, landed near Benedict on the Patuxent River in southern Maryland. Ross and troops then began to advance on Washington, some 40 miles away.

On the 24 August at Bladensburg, Maryland, Ross encountered a numerically superior American force commanded by Major General William H. Winder. Winder’s force consisted of 6,500 militiamen and 400 sailors and marines. Ross’s advance guard of 1,500 men routed the American force which fled in panic and disarray, so much so that the battle became known as the ‘Bladensburg Races’. The American militia fled through the streets of Washington, less than nine miles away. Only the American sailors and marines under the command of Commodore Joshua Barney acquitted themselves with honour.

Later that day the British entered Washington virtually unopposed, James Madison, the 4th President of the United States, along with the rest of the federal administration, having fled.

Ross sent a party under a flag of truce to agree to terms, but they were attacked by partisans from a house at the corner of Maryland Avenue, Constitution Avenue, and Second Street NE. This was to be the only resistance British troops encountered. The house was burned – the only private house to suffer that fate – and the Union Flag was raised above Washington.

The British set fire to the Capitol (seat of the Senate and the House of Representatives), the Library of Congress, the Executive Mansion (or White House), the US Treasury and other public buildings. The Americans themselves set fire to the Washington Navy Yard, founded by Thomas Jefferson, to prevent the capture of stores and ammunition, and the 44-gun frigate Columbia which was then under construction. For whatever reason the British spared the Marine Barracks, a decision often assumed to have been a chivalrous tribute to their exemplary conduct at Bladensburg.

The spirited conduct of Dolley Madison, the President’s wife, provides a stark contrast with that of the American political and administrative elite. ‘The First Lady’ stayed in the Executive Mansion long after government officials (including her own bodyguard) had fled and is credited with saving several historic paintings, notably the Lansdowne Portrait, a full-length painting of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, and various important artefacts. Mrs Madison was eventually prevailed upon to leave the Executive Mansion only moments before British troops entered the building. There the troops found the dining hall set for a dinner for 40 people. After consuming the banquet, they took souvenirs (including one of the president’s hats) and then set the building on fire.

The British occupied Washington for approximately 26 hours and then returned to their ships.

The Americans have always regarded the British raid on Washington as retaliation for Brigadier General Zebulon Pike’s burning of York (now Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada (now Ontario), in the spring of 1813. Actually the British attacked Washington for ‘its likely political effect’ rather than mere retaliation for York. By attacking their enemy’s seat of government, the British were anticipating the Prussian soldier and military theorist Clausewitz’s understanding of the relationship between political objectives and military objectives in war, as set out Clausewitz’s military treatise Vom Kriege (published posthumously in 1832 and translated into English as On War): ‘Der Krieg ist eine bloße Fortsetzung der Politik mit anderen Mitteln’ (War is merely a continuation of politics by other means).

In September 1814 Ross mounted a raid on Baltimore while the Royal Navy attacked Fort McHenry. The American militia men, defending Baltimore from behind entrenchments, on this occasion acquitted themselves well and succeeded in repulsing Ross’s force and Ross was mortally wounded by an American sniper. Fort McHenry successfully withstood the Royal Navy’s bombardment, an event which prompted Francis Scott Key to write ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’.

American success in defending Baltimore and Fort McHenry offset the humiliation of the brief occupation of Washington and the destruction of so many of the city’s public buildings. The Executive Mansion sustained extensive damage. Only the external walls remained and, except for portions of the south wall, most of these had to be demolished and rebuilt because they had been weakened by the fire and their subsequent exposure to the elements. Unfortunately, there would appear to be no substance to the myth that the Executive Mansion was painted white to conceal the scorch marks. The Executive Mansion had been painted white since its construction in 1798.

Ross died while being transported back to the ships. After his death, the general’s body was stored in a barrel of Jamaican rum and shipped to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where he was buried on 29 September 1814.

Major General Robert Ross was the first (and to date only) soldier to capture Washington, a feat which eluded even great Robert E. Lee and the legendary Army of Northern Virginia fifty years later. Admittedly, Lee probably would not have wished to burn the American capital. Ross was also the first commander to defeat a full US army in the field.

There is a very fine memorial (dating from 1821) by Josephus Kendrick to Ross in the south transept of St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Ross is also commemorated by a 100 foot granite obelisk erected in 1826 near his birthplace at Rostrevor. As an augmentation of honour the Ross family’s coat of arms was granted a second crest in which an arm is seen grasping the stars and stripes on a broken staff; and the family name was changed to Ross-of-Bladensburg.

Reconstruction of the White House began in early 1815 and was finished in time for President James Monroe’s inauguration in 1817. Reconstruction of the Capitol did not begin until 1815 and it was completed in 1864. Thomas Jefferson later sold his extensive personal library to the government to restock the Library of Congress.