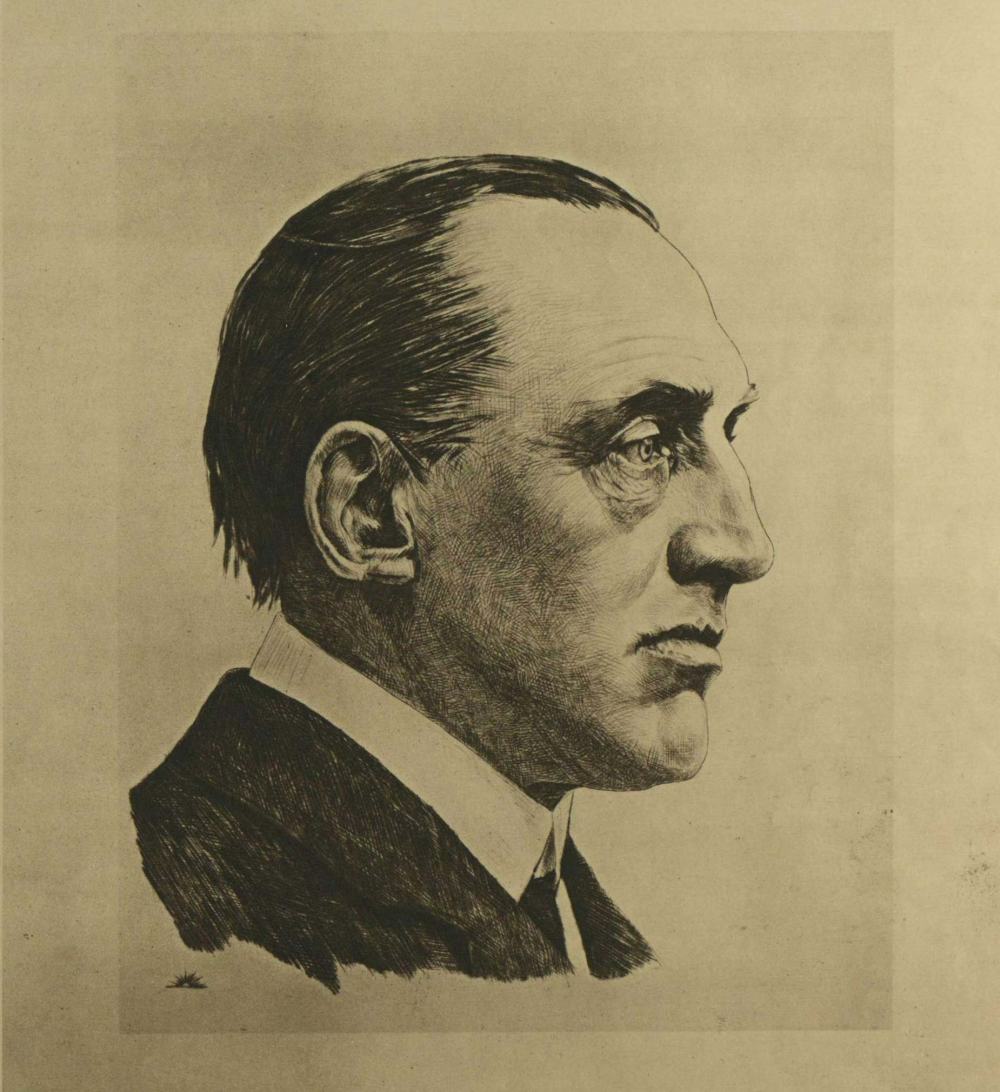

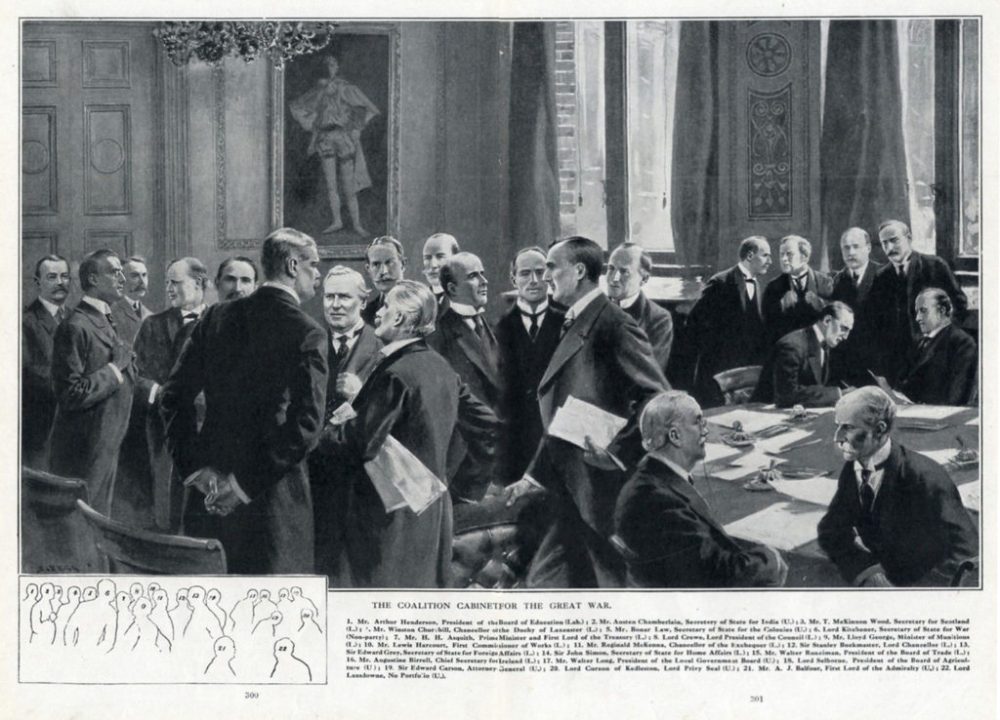

‘More than any single person’ (in the words of the historian Robert Blake), Sir Edward Carson was responsible for the fall of Asquith’s administration and the formation of the Lloyd George coalition government in December 1916. Lloyd George told Frances Stevenson, his mistress, personal secretary and confidante who became his second wife in October 1943, that he had no particular desire for the premiership and that he would have been happy to allow Asquith to run ‘his show (i.e. the Cabinet)’ but he did want control of the war effort.

Lloyd George wished to achieve this through the creation of a small war committee, a structure which Carson had also advocated, for the more efficient management of the nation’s manpower and material resources.

Asquith resigned as Prime Minister in early December 1916. Although he may have regarded the move as essentially tactical, it proved permanent and Lloyd George became Prime Minister in his place – as Carson wished.

Lloyd George offered Carson the position of Lord Chancellor, the greatest prize available to a member of the legal profession but Carson declined and indicated his desire to become a member the war committee (which was to become the War Cabinet) without portfolio.

Lloyd George originally intended appointing Lord Milner, a Liberal Imperialist with radical views which corresponded closely to Lloyd George’s own on domestic politics, to the role of First Lord of the Admiralty and appointing Carson to the War Cabinet. For whatever reason (and Lloyd George claimed he was pressured into the switch by the Conservative Party), Lloyd George changed his mind and appointed Carson to the Admiralty and Milner to the War Cabinet. Thus Carson held ‘one of the most demanding of wartime offices’ at a critical juncture of the war.

In his entry on Carson in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, D. George Boyce observed Carson ‘proved a surprisingly ineffective minister … Carson’s real power lay, as it did in his legal career, in his strength of critical attack’ and in doing so Boyce is simply reiterating the conventional wisdom on the subject.

Keith Grieves in his book, Sir Edward Geddes: Business and Government in War and Peace, writes that ‘He [Geddes] was unimpressed by Sir Edward Carson’s somnolent political leadership as First Lord of the Admiralty and felt that an unwillingness to alter existing, largely pre-war procedures had resulted in an extreme form of naval defensiveness, which the scale of merchant loss symbolised.’

Are these assessments accurate? Are they not shaped by taking Lloyd George’s extremely self-serving post-war memoirs at face value and Sir Edward Geddes’ equally egotistical self-evaluation of his achievements as Carson’s successor? It is highly significant that Winston Churchill in his history of the First World War – The World Crisis gave Carson full credit for the measures he took as First Lord of the Admiralty.

As new First Lord of the Admiralty, Carson very quickly forged an excellent working relationship with Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, the new First Sea Lord.

Both men formed a high opinion of each other. Of Jellicoe, Carson recalled, ‘He was in my opinion the best man at his job that I met with in the whole war for knowledge, calmness, straightness and the confidence he inspired in his officers.’ Jellicoe in his memoir entitled The Crisis of the Naval War wrote of Carson, ‘His devotion to the naval service was obvious to all, and in him the Navy possessed indeed a true and powerful friend.’

Their period in office coincided with mounting U-boat attacks on Allied shipping. In last four months of 1916 U-boats had doubled the average monthly losses in Allied and neutral merchant shipping from 75,000 tons to 158,000 tons. During 1916 the number of U-boats in service rose from 58 to 140. In early 1917 the situation became even more grim because in January 1917 the German High Command decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare. By sinking enough merchant shipping, the Germans hoped to bring the United Kingdom to her knees and starve the country out of the war. Although unrestricted submarine warfare carried with it a high risk of provoking United States entry into the war, the Germans believed it was a risk worth taking because meaningful United States intervention in the conflict would come too late. Unrestricted submarine warfare began on 1 February 1917.

With the benefit of hindsight, we know that the answer to U-boat peril was the introduction of the convoy system. However at the time there was genuine concern that a convoy presented a larger and easier target to U-boats, and was more difficult to defend, raising the prospect of increasing rather reducing the submarine threat. It was also felt that the difficulty of coordinating a rendezvous would maximise the vulnerability of merchant ships when they were in the process of assembling. There were reservations too about whether the skippers of merchant vessels could manoeuvre in company, not least because different ships would have various top speeds. And finally could they be realistically expected to keep station?

Nevertheless, in January and February 1917 Carson and Jellicoe introduced the convoy system on the Scandinavian coal and trade routes to see if the convoy system would work. In mid-April 1917 they introduced a new convoy route to Gibraltar.

On 30 April 1917 Lloyd George – according to his memoirs which appeared in 1934 – descended on the Admiralty building where he allegedly demanded and won changes. Lloyd George also claimed that Jellicoe had always opposed the convoy system. Asked about this the day after the publication of Lloyd George’s memoirs, Carson did not mince his words in responding, ‘It is the biggest lie ever was told!’ The idea that Lloyd George, after a hard struggle, sat in the First Lord’s chair and imposed convoys on a hostile Board of the Admiralty is a myth of his own creation.

The entry of the United States into the war completely transformed the situation. The United States was able to supply the necessary escort vessels. The system was rapidly organised with such efficiency that, though the losses in shipping remained heavy until the autumn of 1917, the impact of the U-boat campaign was greatly diminished.

The close working relationship between Carson and Jellicoe is a subject for another occasion.

Lloyd George once said of Winston Churchill: ‘He would make a drum of out of the skin of his own mother in order to sound his own praises’. The same might be said of Lloyd George with even greater force. In his memoirs Lloyd George seemed to feel the need to denigrate the efforts of others in order to enhance his own reputation. In many respects, this was wholly unnecessary because his achievements did not require embellishment at the expense of others. His treatment of Douglas Haig – who was dead by the time Lloyd George’s memoirs appeared – conforms to this well-establish pattern.

Carson had few illusions about Lloyd George at any stage in his political career. Comparing Asquith and Lloyd George in September 1916, Carson saw Lloyd George as ‘a plain man of the people’ who ‘shows his hand and although you mayn’t trust him, his crookednesses are all plain to see’. Asquith, on the other hand, was ‘clever and polished’ and knew ‘how to conceal his crookedness.’ In September 1917 Carson appreciated Lloyd George’s ‘considerable driving powers’ but also realised – as many did not – that he had no knowledge of strategy or military operations but was sufficiently deluded to imagine he had. A year later Carson was willing to acknowledge that Lloyd George’s courage, energy and foresight had contributed to the winning of the war but he had the wit to know – as he told Mrs Dugdale (A. J .Balfour’s biographer and niece) – that Lloyd George was ‘a mass of corruption.’